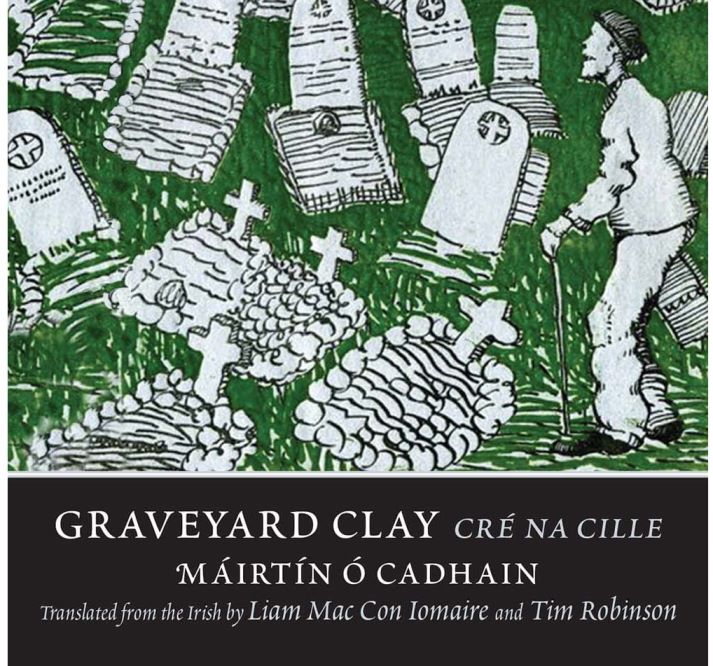

Graveyard Clay

Aistritheoirí: Liam Mac Con Iomaire agus Tim Robinson

Foilsitheoir: Cló Iar-Chonnacht

Léirmheastóir: Máirín Nic Eoin

Foilsíodh an léirmheas seo cheana in The Irish Times, an 9 Aibreán 2016

This translation by Liam Mac Con Iomaire and Tim Robinson is the second English-language version of Máirtín Ó Cadhain’s classic Cré na Cille (1949) to be published by Yale University Press as part of its Margellos World Republic of Letters series, arriving just a year after the publication of The Dirty Dust, the widely acclaimed translation by Alan Titley.

There are several reasons why this major 20th-century novel was not published in English translation prior to this, one of them being the sheer challenge of rendering faithfully the spirit and the letter of this richly idiomatic text comprised entirely of dialogue and featuring an Irish-speaking community in Connemara in the 1940s. Reproducing the black humour and verbal drama of the original was going to be no small feat for any translator. The question of register is central as the translator produces credible versions of characters’ voices as they re-enact, in the graveyard clay, the animosities, jealousies and status envy that governed their lives when they were above ground.

However, the fact that such challenges were surmounted by Norwegian, Danish and Czech translators – versions by Jan Erik Rekdal and Ole Munch-Pedersen appeared in 1995 and 2000 respectively and a Czech translation by Radvan Markus is due in 2017 – alerts us to the fact that what is often at issue in the translation of lesser-used languages in to English is the potential of a translation replacing the original by becoming an authoritative interpretation and a bridging text for further translations in a global literary context.

Thus the decision to commission two translations was a master stroke by Yale, as it avoids canonical status being attached to the first published English version and brings Cré na Cille to a worldwide readership in a manner that encourages ongoing engagement with the original text.

As a novel Cré na Cille was iconoclastic both in subject matter and technique. By mercilessly depicting a west of Ireland community in their own words, Ó Cadhain was employing “caint na ndaoine” (“the speech of the people”, the very medium chosen as model for a new literature in Irish) to challenge idealised notions of rural Irish-speaking Ireland.

The violence and vindictiveness of the language were designed to have a dramatic effect on readers, and the reproduction of the tone of the original is the central challenge in an English translation, particularly as readers of English are so accustomed to the use of strong language in contemporary literature, drama and cinema. Mac Con Iomaire and Robinson have risen to the challenge, while remaining faithful to the cultural context of the original Irish.

Graveyard Clay is a very precise rendering of the speech patterns and earthy vocabulary of Ó Cadhain’s Connemara characters, employing a rich but markedly non-regional form of English. Apart from usages such as “Faith then . . . ” (as a translation of “M’anam go . . . ” or “M’anam muise”) and “Musha” (for “Muise”), which is explained in a footnote, and a number of examples of structures based on the Irish-language copula (“It’s her daughter has left me here twenty years before my time” for “A hinín a d’fhága anseo mé fiche bliain roimh an am”), the translation does not attempt to reproduce the syntax or phonology of Irish-English as it may have been spoken in 1940s Galway. With the single exception of “boreen” (for “bóithrín”), the translation eschews borrowings from Irish which were common and still exist in rural Galway dialects of English.

The decision not to translate names (retaining the Irish spelling and genitive structure Caitríona Pháidín, for example) and the decision to retain the Irish-language structure of certain place names (the Glen of the Pasture for Gleann na Buaile, Wood of the Lake for Doire Locha) are strategies adopted to draw attention to linguistic differences rather than eliding them.

The translation of invective is always challenging and Mac Con Iomaire and Robinson have opted for literal translations of the many derogatory terms used by Ó Cadhain’s characters. While most of the English terms chosen are very effective, the full force of the original is lost in certain instances, as in the regular use of “pussface” for “‘smuitín”, a derogatory term based on “smut”, sulky expression or huff, and the use of “bitch” for the stronger “raicleach”, a violent, overbearing, brawling woman.

As characters speak and interrupt each other without introduction in Cré na Cille, readers rely on consistency in mode of address and on repetition of particular phrases and pet topics to differentiate between them. The translation is very successful in this respect. The highly stylised passages at the beginning of certain sections of the book, where the Trump of the Graveyard speaks out as from the clay itself, requires a very different style, more poetic and sonorous than the voices of the dead.

Again, Mac Con Iomaire and Robinson’s version of these is exemplary in its fidelity to the tone of the original, where metaphorical language borrowed from biology, agriculture, and the crafts of sewing and writing is employed to foreground the novel’s existential concerns, particularly the sense of the human as mere matter in the cyclical process of birth, growth, decay and death:

Anseo sa gcill atá an pár arb é gréasán aislingí an duine a chuid friotal doiléar; arb í caraíocht dhúshlánach an duine a dhúch tréigthe; arb iad aoiseannaí uallacha an duine a chuid leathanach dreoite . . .

Here in the graveyard is the parchment whose obscure words are the web of mankind’s dreams; whose faded ink is mankind’s defiant struggle; whose withered leaves are the ages of mankind’s vanity . . . Overall, Ó Cadhain’s linguistic tour de force has been very well served in this meticulous translation. It will be deeply satisfying for readers familiar with the original and will be of huge value to those struggling linguistically to access it. It should also serve as a useful bridging text for translations into other languages and will be a suitable version for the production of dual-language editions of Cré na Cille.

When the centenary of Ó Cadhain’s birth was being celebrated in 2006, many commentators and readers recognised the need for annotated versions of his work and in particular notes that would clarify historical or mythological references or explain unfamiliar cultural content.

Such notes are provided here, making it an invaluable addition to Ó Cadhain scholarship. There are also insightful introductions by both translators and a bibliography featuring Ó Cadhain’s major publications and important works of Ó Cadhain criticism.

Irish-language readers recognised from the outset that Cré na Cille was a major work of literature. It heralded a new freedom of expression for Irish-language writers, and it has generated more critical commentary internationally than any other single 20th-century title in the language.

The appearance of Graveyard Clay marks another major milestone in the book’s publication history. Like the best of translations, we can expect it to stimulate an ongoing dialogue with the original and to ensure the place of Cré na Cille in the wider multilingual field of comparative literary studies.